Acceptance Speech

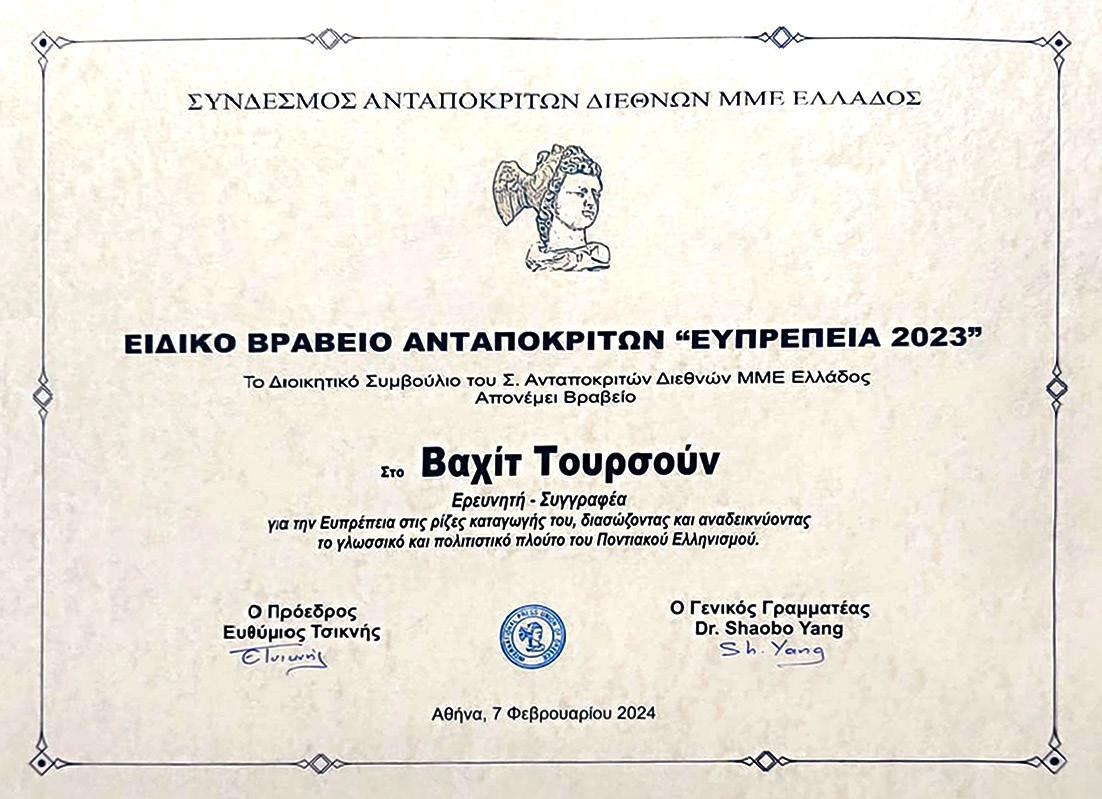

My acceptance speech for the “Evprepeia (Decency) 23” award, presented by the International Press Union of Greece, delivered at the European Parliament Office in Athens, in recognition of my Romeika–Turkish Dictionary.

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen.

My heartfelt thanks to the International Press Association of Greece for this honor. It is especially meaningful for Pontus, where our language is not only history—it is still spoken by thousands today. To be invited to speak about this living language is a privilege.

I have described the making of the dictionary in a two-page note I submitted to the Association, which you may read. Tonight, allow me to add a few things that do not fit into footnotes.

I have lived in Greece since 1989 and began collecting Pontic (Romeika) words and phrases in the early 1990s. Research trips to Pontus were essential—until things became complicated. I was accused by the Turkish authorities of separatist activity, and the State Security Court issued a warrant. For years I could not visit the village where I was born.

Like the Argonauts in the Propontis, I navigated rough waters—police, ministries, services with many names and no faces. At the same time, although I lived and worked in Greece, I often lacked a residence permit. For long stretches after 1993 I stayed indoors to avoid deportation, leaving only for work—and even then with fear.

Paradoxically, that confinement helped. I devoted myself to recording Romeika, and—with the arrival of the internet—speakers from my village and the neighboring valleys found me. I asked everyone, young and old, to write down every word they could remember. I asked about grandparents who still told jokes and stories in Romeika. My persistence was sometimes embarrassing; but around seventy people helped—some of them no longer with us. Their voices live on in these pages.

After seventeen years, in 2011, I returned to Turkey for two years. I became a hunter; my prey was words and idioms. I had already gathered a great deal since 1992, but I knew there were thousands more waiting in the hills and kitchens and memories of Pontus.

The dictionary itself deserves a book about its making. In 2015 I was hospitalized with a vascular malformation in the brain. Three dangerous operations were planned. I was anxious—not only for my life, but for the words. If things went badly, the work could be lost. After the first surgery I decided to postpone the second until I had sent the dictionary—the dream of my life—to press.

I am neither a linguist nor a philologist, so I had to become a student again: modern Greek grammar, ancient spellings, Turkish grammar for accurate translations, hundreds of texts. I even designed an alphabet of diacritics and turned to the International Phonetic Alphabet to explain the sounds.

That is how this book was made: 14,400 headwords and 8,500 phrases, written in the daytime and in many, many nights. If illness had not hurried me, I would gladly have spent more years adding entries and examples. Perhaps I still will.

Thank you for listening—and for honoring not only me, but a language that continues to live.